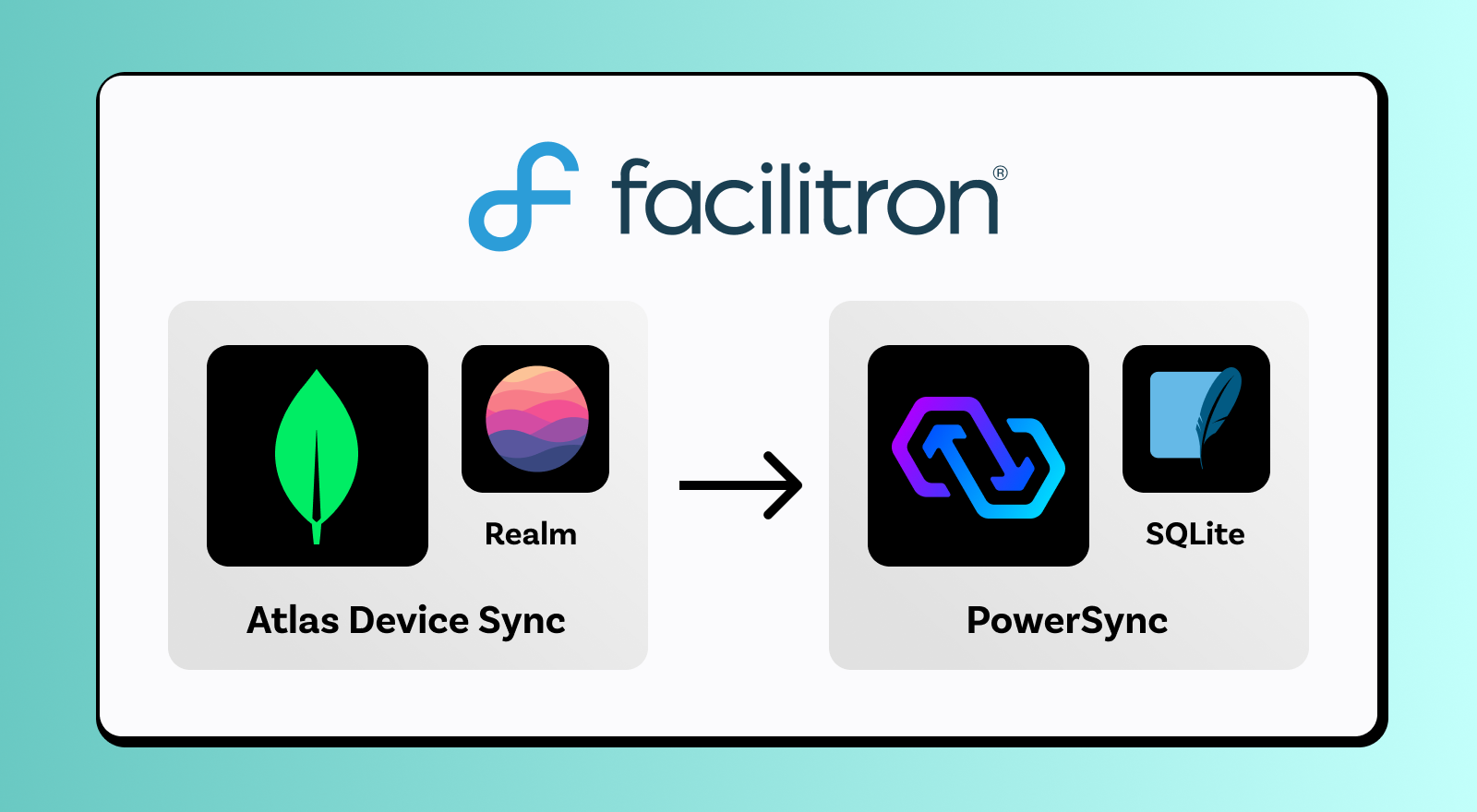

When MongoDB announced the deprecation of Atlas Device Sync and Realm in September 2024, many teams were affected — some were still just evaluating Atlas Device Sync, some were busy integrating it, and some were already running it in production. If you were in the latter category, you naturally faced the biggest challenge.

Facilitron found themselves in this category. They considered a few options. One was to migrate to an alternative solution recommended by MongoDB: Ditto and PowerSync stood out. Another was to build their own home-brewed sync solution. They even considered whether they really needed sync in the first place. Ultimately, they successfully migrated to PowerSync in only a few months. Their engineering team, led by Dima Bronin, was kind enough to share their experience so that others who find themselves in the same position could benefit.

Facilitron operates a national marketplace for community use of public spaces—helping school districts and municipalities manage access, scheduling, and policy compliance.

Facilitron and their Build app

“Facilitron is the Airbnb for public facilities,” says Steve Gaylord, a senior engineer who oversaw the migration to PowerSync. He explains that federal law requires that many public facilities be made available for rent, but that it’s often a schlep for both renters and administrators. Facilitron provides a platform for solving that problem, but as Steve continues: “one of the differentiators is we are not just a software company.”

A key in-person service Facilitron provides is scheduling a team to go on-site and collect data, validate amenities, and capture professional photos for the facility listings. The app that they migrated to PowerSync manages this on-site data collection workflow—part of Facilitron’s operational process for documenting and publishing facilities within its marketplace.

The Facilitron app provides a structured way for remote teams to capture facility data, while automatically uploading data to a central database. “Keep in mind that all of this has to work offline, seamlessly between network states, with teams of 4-5 capturing hundreds of data points each.” says Steve.

Pre-migration app stack for the Build app:

Migration Process

Deciding between alternatives

It was clear that sync and offline-first functionality were non-negotiables for the Build app. They considered three options for the migration:

- Ditto

- PowerSync

- A home-brewed solution

“On paper Ditto looked more promising,” says Steve, “but then we started talking to you all and you guys were so great and proactive that it really gave us a sense that you knew what you were doing.”

Dima adds two other important considerations:

- “You guys are open source.” After their experience with Atlas Device Sync, it was critical for Facilitron to know they could self-host the sync part of the stack.

- “We couldn’t justify the ROI for building something in-house. There is so much that comes into play with conflict management and conflict resolution that we don’t have the bandwidth to be the experts on.”

Migration approach and experience

Islajd Meco and Kyr Korota were the two engineers responsible for the migration. Islajd's focus was on the backend side of things and Kyr looked at the frontend.

On the frontend, the plan was to migrate bit-by-bit and validate functionality as they went: “We did it screen by screen to not break the whole system,” says Kyr. Realm is a NoSQL client-side database, whereas PowerSync uses SQLite on the client-side. This required some data types to be migrated. For example, a facility object contained JSON arrays that had to be transformed to their component parts to work well in the relational database setup. “We would migrate data types and audit the data side-by-side,” says Kyr. “We had two versions of the app for this… This was the right approach.”

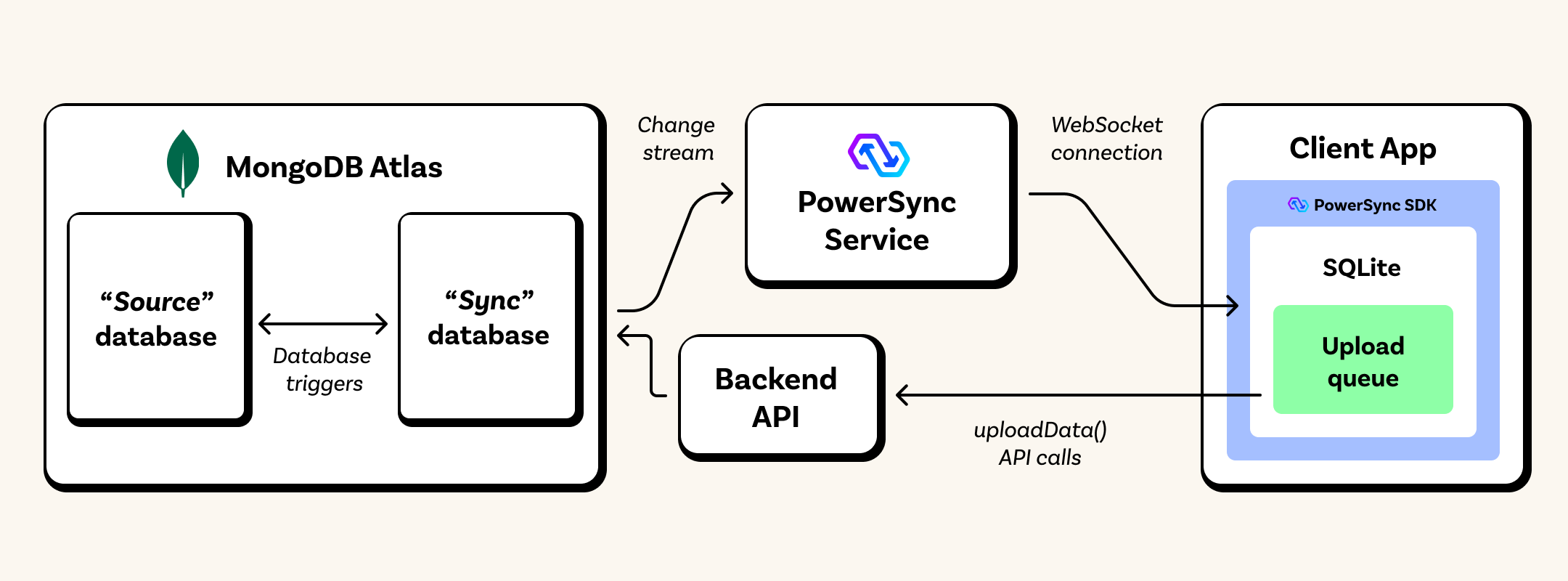

On the backend, the existing setup made use of two MongoDB databases: a source database and a “sync database” — a replica wired up to the sync engine. They did this for two reasons. The first is that not all data in the source database was relevant to the mobile application and so creating a partial replica simplified the sync implementation. The second is that isolating the sync database provides another layer that can be used for data validation and transformation.

This turned out to be useful for the migration to PowerSync, which for example requires some data to be denormalized (this is true as of late 2025: support for syncing from incrementally materialized views which would reduce the need for denormalization is currently in development). “Every time we have a new operation in the sync database, we have triggers that normalize the objects and update the source database.” says Islajd. In fact, there were no unexpected backend changes necessary to implement PowerSync: “Everything was the same as with Realm.”

Post-migration app stack for the Build app:

Architecture and data flow with PowerSync

- PowerSync connects directly to the MongoDB “sync database”, where it reads the change stream to replicate relevant data to the PowerSync Service. This is based on Sync Rules (and soon, Sync Streams) which declaratively define what data should be replicated and synced to users.

- The PowerSync client SDK in the React Native app maintains a WebSocket connection with the PowerSync Service, and streams data in real-time to the client-side where it is persisted in SQLite.

- Any client-side mutations are immediately written to the SQLite database and also placed in an upload queue.

- Developers define an %%uploadData()%% function that specifies how client-side mutations should be uploaded to a backend API that applies changes to the MongoDB “sync database”. The PowerSync client SDK automatically invokes the %%uploadData()%% as needed.

- The sync database syncs with the source database through database triggers.

Advice for others migrating from Atlas Device Sync

“I would give the typical migration advice for any project,” says Dima. “Start small, do an MVP, make sure you get your foundation set and you understand how the system works.” Having a PowerSync team available for their engineers to work with has been crucial to their success: “Sometimes you go into a migration thinking that you can figure it out. It makes a difference to have a contact — don’t discount that.”